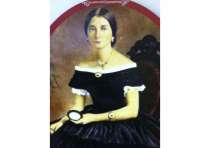

Witty and highly educated, Kate Carney (1842-1930) of Murfreesboro described secession and Union occupation in her Civil War diary. An ardent Confederate supporter, Carney deeply resented the arrival of Union troops and shunned any association with them, whom she referred to as “rogues,” though other residents of the town were more conciliatory. Carney’s diary provides ample evidence that Murfreesboro was a divided community. Carney was the daughter of Katherine Wells Lytle Carney, a descendant of Murfreesboro founder Captain William Lytle, and Legrand Carney, a successful merchant and landowner. Shortly after Union forces occupied Murfreesboro in March 1862, they imprisoned Legrand Carney for about a month. Thereafter, the family had a strained relationship with Union authorities. On the one hand, they accepted Union officers as dinner guests, boarded an ill officer, and allowed Union soldiers to take flowers from their garden. On the other hand, they refused to take the oath of allegiance, sheltered Confederate escapees, and brought provisions to Union prisoners even after being ordered to stop. As a young woman without family obligations, Kate Carney was free to be more adamantly anti-Union than her parents. Kate defiantly refused to interact with Union officers and used household slaves as intermediaries when the men came to the house. Carney commented on the divergent reactions to Union occupation and war news within her father’s household, as the slaves welcomed occupation and became despondent when learning of any Confederate military success. Carney’s diary provides a dramatic account of the Confederate raid on Murfreesboro led by Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest on July 13, 1862. She recounted how she hissed at Union soldiers as they retreated through the Carney’s property north of the town square. When the fleeing men asked Legrand Carney to shelter them, he told them to move on. The next day, Kate Carney wrote, “We can scarcely realize the joy of being free,” although she acknowledged that it would be short-lived since the Confederate troops did not remain after the raid. Carney’s surviving wartime diary concludes at the end of July 1862 (when she married in 1875, she burned the later volumes).